5 for 5000: profits are good, actually

- Publish Date

- Authors

- Justin Searls

This post is the third in a five part series celebrating Test Double’s five-year run on the Inc. 5000 list of fastest growing companies:

- Widen the Goalposts for Success

- The Customer is Usually Right

- Profits are Good, Actually (this post)

- Do Right by Everyone

- Find your Leading Indicators

Revenue isn’t the whole story

(I can’t believe I have to say this, but) profitable companies are better equipped to survive over the long-term than unprofitable companies.

The Inc. 5000 list measures companies by revenue, not profit. And they’re not alone: it’s all too common to see revenue numbers touted and celebrated while profitability is routinely downplayed. Indeed, you can cook up some really impressive revenue numbers in the short-term if you’re willing to lose money on every transaction, but odds are you don’t have the requisite millions of dollars of venture capital funding to burn. And while the leaders of a handful of companies like Amazon forgo profit and instead plow every surplus dollar into increased market dominance, it’s a lot easier to swallow when the founder is nevertheless able to unload $1 billion in shares for cash each year.

The fact is, when it comes to the survivability of most companies, profitability is paramount. Every dollar of revenue that remains after subtracting costs is a dollar that can increase a company’s capacity to persevere under duress, whether that money is saved for a rainy day or invested as a hedge against potential downturns. Test Double is incredibly fortunate to have so far endured the economic shock wrought by COVID without having to lay anyone off, but it’s only been possible because we’ve designed every aspect of the company’s operations to yield enough profit to give us ample margin for error.

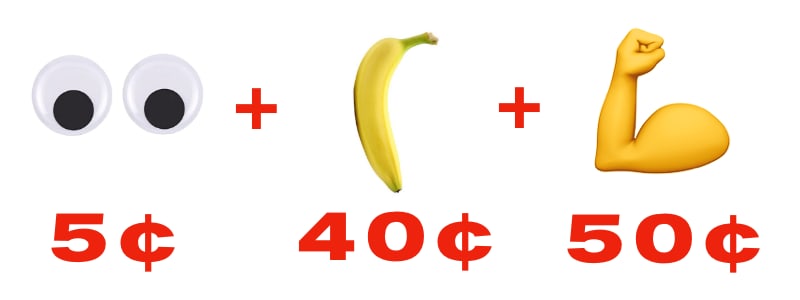

If the significance of profitability with respect to a company’s operational

resilience has never quite made sense to you, here’s a silly example. Suppose

you start a company that buys googly-eye stickers for 5¢ and bananas for

40¢, then glues them together with 50¢ in labor costs:

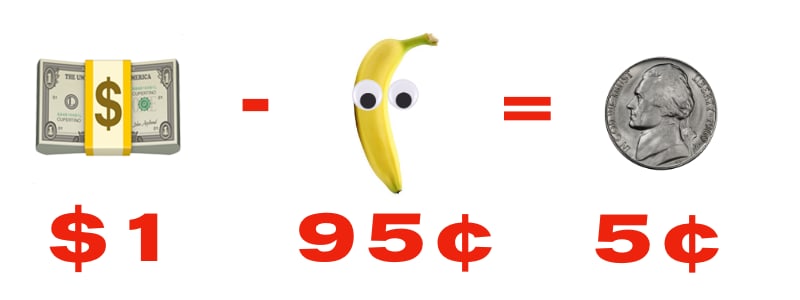

If you sell these creepy bananas for $1, their marginal cost of 95¢

means you’ll be left with 5¢ after each transaction:

Put differently, your absurd business will be operating at a 5% profit margin. You didn’t get into this business to exploit anybody, so a 5% share of the revenue might seem like a fair cut.

Against all odds, suppose your business takes off! Say you sell 1,000 bananas in your 1st year, 10,000 in your 2nd year, 100,000 in your 3rd year, and 1,000,000 bananas in your 4th year. That’s an astounding track record of 1,000% annualized revenue growth! You’d definitely make a few lists of fastest-growing companies.

But even when you manage to hustle your way to a million bananas sold, your razor-thin 5% margin means your business is only generating $50,000 of profit. Even though that’s a decent income, the reality is that it doesn’t leave much room for error! If a batch of 125,001 bananas arrives rotten or if the marginal labor costs for each banana increase from 50¢ to 56¢, then your 5% profit margin will be wiped out and you’ll find yourself operating at a loss. Because of your narrow margins, balancing your cashflow would be a high-wire act, leaving you with little freedom of movement to pay your bills or make payroll whenever costs increase or sales decrease. A single unfortunate event could be all it takes to put your banana stand out of business.

So then, higher profitability can help companies weather the unexpected and stay in business. But how do you determine the right level of profitability to target? And what can you do to hit a target profit margin?

The answer will vary from business to business, but if your objective is stable long-term growth that can withstand adversity, then a target profit margin can be derived from some worst-case planning. What’s your doomsday scenario? For us, for a long time, it was, “every consultant hits the bench simultaneously,” such that costs remain constant but we’re booking zero revenue. And how long do you want to be able to survive (read: make payroll) under those apocalyptic conditions? For us, the answer was “about three months”. (Any longer than that and we’d all probably be better off finding a different line of work.) So we did some simple arithmetic to arrive at the percentage of profit we’d need to save a rolling three months of payroll in cash; then we increased our prices, contained our costs, and throttled our hiring to ensure we could keep that war chest funded. The specific percentage of profit Test Double was generating mattered much less than what it was buying us: financial security.

We have the 2008 financial crisis to thank for teaching us these lessons. Seeing how quickly our employers missed payroll or were forced to lay off workers was a real wakeup call. For most people, when they accept a full-time job offer, they feel a sense of security that it represents a durable promise from their employer of stable, dependable income. But the truth is, unless the employer has put in the work to establish firm financial footing—and shockingly few have—that sense of security is an illusion.

We wanted to do better.

This is why we designed Test Double to be predictably, consistently profitable. When we hire people, we are committed to backing any sense of job security with real financial security. And we follow through by sharing our finances with the team—in good times and in bad. It’s our dedication to sound financial planning that reassures our people that it’s safe to continue to focus on doing their best work. The next time you’re interviewing for a job, ask them about their finances and which numbers are shared with the staff. Seriously! Whether a company routinely shares its financials with its staff says a lot about what they value, and absent that I’d be leery of any sense of job security they might promise.

And one last thing. Once a company has put their profits to work to build an engine for stable, predictable growth and provide firm financial footing, it’s entirely reasonable to ask where those profits are going. Eight years in at Test Double, we decided that it was time to share its profits in a meaningful way with our people by transitioning from a two-person partnership into a 100% employee-owned company. We did this not only because we believed giving people equity was the right thing to do, but because it was the best way to retain the most important ingredient in our next stage of growth: our people. And while there are no one-size-fits-all answers, when you start thinking about profits as a tool for tackling the most profound problems facing your business, you might be surprised just how useful they can be.

[Continue to part 4: Do Right by Everyone]

Justin Searls

- Status

- Double Agent

- Code Name

- Agent 002

- Location

- Orlando, FL